On a very optimistic day I can imagine Macaronis, not as a parking lot, but managed as a sustainable resource preserving its value and the purpose of travelling such a long distance. A destination that remains attractive with a finite number of surfers at any one time taking turns to catch waves, governed by an openly accessible waiting list in which all stakeholders have faith. In this vision, each visitor would pay a substantial daily fee into a securely managed 'Silabu Trust', which would disburse the perpetual income from surfing visitors for education, medical services, and infrastructure for the Pagai villages. If surfers could achieve that goal we would avoid following the 'race to the bottom' that has charaterised the waves in Nias and that the logging companies pursued in the Mentawai forests.

A 20th century ecologist, Garrett Hardin, called the market failure scenario currently occurring at Macaronis the “Tragedy of the Commons”. It was first spelt out in 1837 by William Forster Lloyd, a Fellow of the Royal Society, in describing the fate of common grazing lands used by all the livestock farmers in a small village. In Lloyd’s scenario, each farmer has a right to use the common resource, and each keeps adding more livestock because the marginal cost of doing so is zero and the short-term individual gains worthwhile. All the users know this is unsustainable but lack any mechanism for restraint, so the lands are overgrazed, devalued, and the farming economy ultimately fails.

Textbook stuff. Yet it’s hard to argue with the idea that all surfers should be free to use the Mentawai waves, just as it would be a nice principle to allow all farmers to graze their cattle and sheep wherever they liked. So the charter boats and land resorts keep adding more livestock to the surfing commons, and the value of 'surfer’s gold' plummets.

Britain in the nineteenth century addressed the Tragedy of the Commons by making the commons private property. The wealthy land-owners limited access to the private property, and set a fair value for use through the free market. It preserved the lands, but was also a market failure as it sent most of the population into famine.

Uncrowded, perfect waves have much more esoteric value than food, but in the case of Pasongan what is at stake is the economy, health, and education of the surrounding villages. Can the surfer's version of the tragedy of the commons be avoided by a private property market solution?

Probably the first application of privatized surfing was for the perfect waves of Cojo Point and other breaks along the Hollister Ranch, west of Santa Barbara in California. Subdivision of The Ranch to well-heeled surfers occurred in the 1970s at the time that Southern California surf was becoming overcrowded. Passing through in December 1978, I happened to be lucky enough to get an invite from a friend of a friend one afternoon, surfing an uncrowded Californian line-up with millionaires who could afford to buy a parcel of private paradise. Good if you can get it, but it didn’t sit well with my own belief that surf should be free.

In 1978 I also had a first-hand view of the implementation of the private surf camp solution applied for a few years to G'Land by Californian Mike Boyum. I visited G'Land holding a legal permit of access from the head office of National Parks in Bogor and paid no access fee to Boyum. His imposition of exclusive access to G'Land had no basis in Javanese law as far as I could tell.

By contrast, the private surfing resort at Tavarua in Fiji was based firmly on longstanding Fijian law governing the use of coral reefs adjacent to land owned by villages and their chiefs. Tavarua Resort was developed by Santa Barbara surfer, Dave Clark, and later with San Diego partner Jon Roseman, through an exclusive lease agreement with the nearest villages of Momi and Nabila that had legal rights to the use of the Cloudbreak and Tavarua island reefs. Like it or hate it, from 1982 until 2010 the resort of Tavarua kept the perfect waves at Cloudbreak from turning into 'Crowdbreak'.

Whether it was a good or bad model depends on your point of view. If you were a villager of Momi or Nabila, or a surfer with the connections to get a week or two slot on Tavarua, it was a model of sustainability. For the villages it provided sustainable income, training, and better living standards. For a surfer with a Californian connection, it was worth saving for years to pay the market rate to surf the barrels of Cloudbreak with a friendly, well-regulated crew of other surfing guests.

Comments

I'm loving these series of articles but this one somehow leaves me with mixed feelings. Having most of this occurring within my surfing life I feel a little sad with the direction surf tourism has headed. I must be one of the few surfers on earth who has never been to Indo even though I've had many opportunities. Pun intended but I kind of feel like I've missed the boat. I look at vids of pumping Mentawais and think just how much I'd love to surf those beautiful waves but then see how crowded they are and think how lucky I am here surfing pretty good waves (albeit farking freezing) with just a couple of blokes out.

I know a bloke whom I wouldn't call a friend who goes every year, snarling, angry, arrogant, selfish, shocking surf manners who takes pride in sharing how he starts and finishes his trip in Bali so he can 'smash a few of the local girls for hire', a walking firecracker of a bloke. The kind of fella who probably adds to the tension at a place like Macaronis as mentioned above. Multiply that by I don't know how many but I'm guessing that he's not the only one like that who goes there.

Maybe I'm getting old but I keep telling myself I have to go there one day but how amazing would it have been to rock up all those years ago to surf something so truly special without snapping too many twigs.

Go to Indonesia Zen Again. Not to prove anything, not to become a more complete surfer, or to tick a place off your bucket list, just go and smell the cloves, stumble through some basic words with a smiling local, and get repeatedly barrelled in bath warm water. If Mr Firecracker crosses your path you wont even care.

I think everyone feels that way, i felt i had missed the boat first time i went to Indo about 20 years ago, I don't want to encourage people to go to the Mentawais or other outer Islands of Sumatra, but even though you may not get Maccas uncrowded there is other waves that don't have big names that can be almost as good and empty.

Interesting read, and good comment Zen.

I've seen places change rapidly from a semi-secret spot into the 'it' wave of the season, both from the perspective of a surfer and that of a resident busybody anthropologist. To put it simply, in the years I have spent surfing and researching across Indonesia I could count the number of surfers on my hands who have had the capacity to glean any understanding at all of place/culture/religion/economy/society, and the impact they were having on it. Their worldview is pointed to the surf, unable to see the forest for the trees.

In essence, the surfing and the pre-surfing communities are two different places, and the two would meet only in economic exchanges in the local warung. Blame language, misunderstanding, arrogance or otherwise, but in most places, surfing does not blend in to local communities, but instead creates entirely new ones. And in that Pasongan ceases being a village in the Mentawai Archipellago, but a world-class left hander known by most only as Macaronis. Kids stop growing up in the fishing/goat hamlets of Gumulharjo and Ketro but instead in the bodyboarders paradise of Watu Karung. Separate economies emerge, the new and lucrative surfing industry almost always led by and for the profit of expatriate surfers. Surf journalists, photographers, videographers and professional Instagrammers come in and re-write the narrative of a place to transform a fishing village with a complex history into a "simple, laid-back town full of fishermen who are happy with nothing." It's transformative in ways that the average surf tourist will never understand.

What's worse, I have seen the people responsible for advertising and commercialising the surfing experience in Indonesia whinge and gripe about the crowds they have created, and that other developers have followed their lead. They then move on to other seldom visited areas to continue the plunder. Like gold miners, a handful of these (mostly Australian) surfers have bought land through intermediaries right across the archipelago in the off-chance that a new road or harbor might make access to these areas easier and thus profitable. We've all seen how it works: "screw Bali, come surf XXXX in uncrowded waves with just you and your mates" or the ads telling us to go to the Ments in the offseason to get it uncrowded. It's the most ridiculous, contradictory advertising scheme ever and it unfolds with such frustrating inevitability.

For all their talk, those Bali expatriates are no better. They certainly have their handle on the expatriate gossip mill, on happy hour timetables and tedious stories of gangsters and criminals in Kuta town, but when it comes down to it they are mostly like the bloke Zen described above. They're usually no more understanding of Indonesia as a nation or of adat/culture/tradition as a concept than the average two-week surf tourist. 'Good' expatriates, or let's call them immigrants, certainly exist, but so clued-in to crowds and so part of the fabric, they are mostly invisible.

Indonesia is a career for me so I can't hold every bastard up to the high standards I set for myself, but the arrogance and ignorance in the surf-tourism industry would cause riots if it were held by foreign developers in Australia. Despite the good intentions of most, I am often left cringing. The argument has been made that surf tourism is contemporary colonialism, and I very much agree with it.

Wow.. amazing post Dan.

Terrific post, Dan.

Dandan...a well written post with feeling. I was also fortunate to find a special place but in Bali. Yes, in many ways I fully understand your thoughts and also that of zen. But is this not just a search & discovery of mankind in general. In this case, it is gold for us and for many locals (who were / are fearful of the waters). The paradox I found was that here we were finding nirvana. But the locals looked at us and saw our wealth, our clothes and hence wanted to be like 'us'. Whilst we observed their ways and their land with golden waves. Many of us tried to keep the discovery quiet but that's impossible. Change inevitably rolls on.

Nice Dandandan, you've hit the nail on the head, Mentawai style hammering that is, with that strange song-like rhythm and effectiveness that most westerners will never get their head around. I agree with almost everything you've said, and if you can churn out a comment like that (read: awesome), it'd be great to hear someone with your experience and expertise write an article for Swellnet. After all, it's only the communication of these sorts of ideas that's going to make any difference.

Mentawai's been colonised many times in history, and at the very least the surfing industry there pays surface level respect to local communities (ie. resorts having sikerei come dance, employment etc), its not much and yeah a lot of it's cultural appropriation, but it's a hell of a lot better than those missionary bastards insidiously and deliberately corrupting culture, or the indo government blatantly burning Umma's and banning the tattoos, or the Malaysian palm oil companies. At least there is a bumbling, smiling, lip service from the tourism industry - i'm not saying its great, or that I know the answer, but i'd like to think there's more than one hand's worth of legit surfers out there...

The Mentawai beheaded the first missionary, and yet by the turn of the century 95% percent of the communities had succumbed to Christianity or Catholicism. Is it gonna go the same way with surfing? Are we looking at a another Nias?

Would love to hear your opinion, or read your more of your writing... cheers.

I know what your saying Dan Dan totally agree, but i think Macaronis is probably at the other end of the scale of things compared to Watu Karung and other areas that are blowing up at crazy rates especially when marketed by some as the last uncrowded piece of Indo.

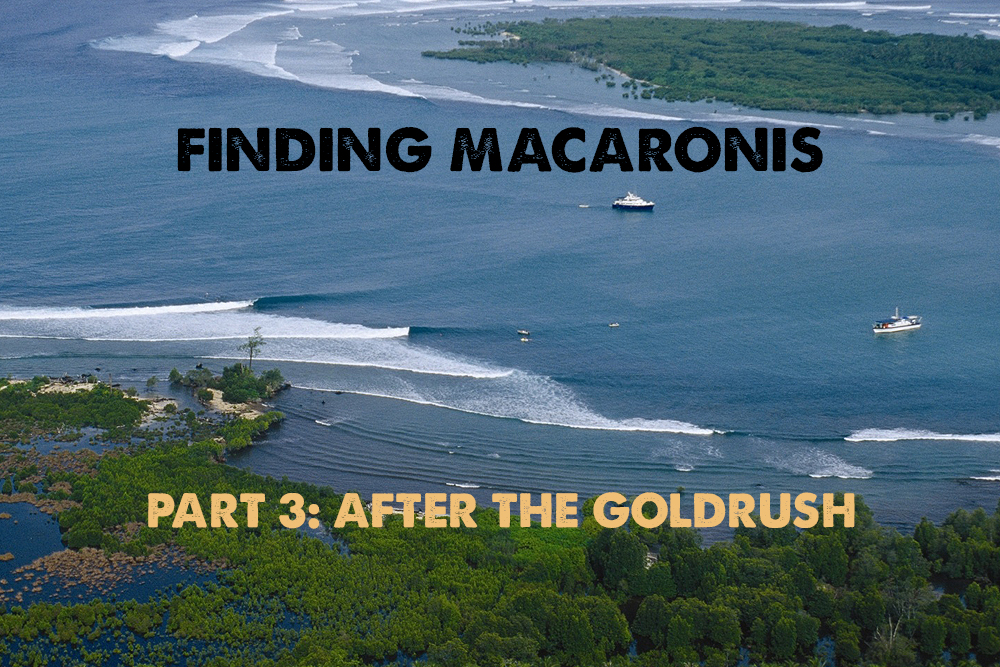

If you look at Macaronis and you consider how long its been exposed to the world and how much and how many surfers have surfed there, physical change and the footprint left behind is kind of small, a small makeshift photo tower on the point, some bouys and off course the resort, the village has had improvements and a path now leads to the resort, but the village apart from being better off now than many other Mentawai villages infrastructure wise and to a degree living standards is still very much removed from the surfing world, even if you look at that photo above take out the boats and it could have been taken back in the 80,s.

Even non physical aspects of change are not that big i guess because the village is rarely visited by surfers as is quite a boat ride from the wave a good half an hour or less if go by new track from resort to village… (Katiet at HT,s is a different beast though being village right on a wave its much more exposed to surfers)

I guess thats one rare good thing about charter boats in that they may exploit an area and sell it like a product (and the Mentawai's as a product is like surfing gold) but they don't change it too much.(don't take much but don't give much back either)

Its interesting what you say about the two communities, I've noticed this even the first time i went to Indo id look to get out of that community built around surfing and venture into what i guess is the true indo, wherever we stayed first trip be it Medewi or Lakeys first thing id do other than surf is go walk the beach or road looking for the real indo.

Its everywhere in Indo its even in Bali walk down some gangs even behind the main drags of places in Legian and you can find areas that feel like they could be anywhere in Indo, the dogs won't let you walk past them without barking like crazy, the old ibu's surprisingly can't speak a word of english, and there is people selling real homemade indo snacks at real prices and don't even look at selling to you.

You can also find it in places like Nias (Sorake) the line between the two worlds there is also a lot closer than you think, you can even draw it at where the owners live or the road out the back, where you have the same thing a lot of the older people can't speak english and even many of the warungs are no different to the ones half an hour drive away or you can even draw the line not in a physical sense but a mental sense at the losmen itself, if you speak Bahasa Indonesia you can be let into a different community.

I guess its just the mentality of most surfers that the focus is on the wave out the front and its all about just surfing or the Bintang in the arvo and for most i guess language creates a divide, I'm glad i don't get stuck in that bubble but in another sense maybe its a good thing that these places are contained and don't spread to deep into the community?.

A bit off subject but its mentioned in the article and comments and as much as I'm not a fan of places like Nias (Sorake) i was sitting there last time i was passing through thinking where it had all gone wrong? and breaking it down.

And i don't think it's as bad as we first thought or people make out people always use Nias as an example of the worse case scenario… but if you break it down the problem is mostly physical with the destruction of the beauty of the area the loss of beach/sand and loss of vegetation some of this is due to the earthquake making things look a bit ugly and other things like the loss of beach/sand is not related to surfers and is due local sand mining of the beach by locals to make concrete bricks or concrete in general.

The loss of vegetation in part also due to Tsunami but mostly just trying to cram in as many losmens as possible and cutting palm trees etc down to get a better view of the wave or ensure they don't fall and damage buildings.

If you break down the other impacts on the community like alcohol or prostitution etc even these are not that bad and are problems seen everywhere in Indo.

For surfers the crowd is a problem but if you look at the crowd in numbers its actually no different to Macaronis, both waves are rare to get empty but possible and generally the crowd normally sit between ten to fifteen to twenty to thirty.

I think if managed even at this stage Nias (Sorake) could be made into a much nicer place its a lot harder now, it would be nice if we could go back and get the losmen owners all to agree to have a ten metre buffer zone of coconut palms between losmen and beach and between losmens, but if the locals were smart even now they could make the area so much more physically nicer if they started a group that ensured the area was kept clean, the place re plated with coconut palm where possible, that nice fine green grass planted, gardens added and a halt of wall to wall development, even replenish the beach and stop sand mining…but sadly it may never happen.

In regard to places like Nias, Telos and Mentawais it should be also noted that outside of the surfing world these places are developing at a crazy rate and its not fuelled by surfing, its just fuelled by general growth, I've noticed huge growth in the Mentawais and Telos in the last ten year even the last five even the last two, just a general population boom and infustructure boom,airport improvements, new roads, schools, shops, houses areas getting put on 24/7 electricity….i think as time goes on and solar technology gets better and cheaper and batteries better and cheaper its going to make an even bigger boom as raises quality of living just simple things like having refrigeration is huge in these places.

Sorry i guess i kinda went off topic a little.

Meanwhile in Melbourne there's an tourism campaign spattered on the trams here about Indonesia, which features a heaving Kandui tube and a surfer getting barrelled in it - and actually captions it as Mentawais.

I was only thinking of the evolution of surf spots, re crowds and property investment yesterday as we visited Nusa Dua. I could not believe the concrete jungle that has overgrown the place in a mere 5 years. The list is growing fast, I wanted to belt some of the hollywood beautiful people at Ulu's the day before, because I have no idea why they're there, in "81 it was just a long hut and a 2k walk with just the surfers and girlfriends making the effort, now it's a place to sip whatevers and ponce off. The same when 10 years ago we checked out Byron Bay after my last visit in'79 and I could not find anything of the old Byron township that drew people to it in the 1st place. This may be the inevitable future of the island chain where Maccas is just one of so many marketable surf spots. There's no one to singularly blame, but if there is no official government management and protection the place will evolve as others have into an almost un-recognisable uber rich playground.

I like our surfing national parks in Australia, where even though the crowds are present the area is protected from further negative development, and as you have to pay an entry tax to to enter Indo one should be imposed to surf these sensitive remote locations, similar to Ron at Cactus, to give something to the locals and keep them and the place sustainable.

wow,

Excellent article and comments all round. This is the reason i return and use this website."The thinking surfer site". Gold stars all round, cheers ld

Some of the comments in this series - If it weren't for the missionary's , at substantial risk of their own lives and a gruesome death - the author at a tender age , many more of the native people , and some of your highly esteemed surfing pioneers , would / may well have , lost their lives , having their heads severed off at the neck - I would consider that a significant contribution worthy of consideration , even here .